I am the tortoise. While all the hares are racing around the track, I’m at the back, being lapped, and lapped often. However, like the tortoise, I will be making up those laps and adding several more long after the hares have crashed.

Endurance running is for us tortoises; but is it healthy or destructive? Are the frequent Facebook shares, tweets, and emailed articles predicting the early death of all marathoners backed up by research? Reviewing the literature, the answer is no, as long as you stay within some limits.

“Well no, actually I don’t. I play real sports. Not tryin’ to be the best at exercisin’.” – Kenny Powers, “Eastbound and Down”

The Good News

The November 2014 meeting of the Society for Neuroscience focused on the two factors that have the greatest positive impact on brain health: aerobic exercise and intermittent energy restriction (IER) or intermittent fasting. (My adventures in IER are coming soon in a series of blog posts.) There are inarguable mountains of data to support the benefits of aerobic exercise and this includes running. Running is associated with improved physical and mental health, stress reduction, weight reduction and maintenance, as well as increased socialization, which contributes its own long list of benefits. New runners report positive lifestyle changes such as improved sleep, improved eating habits, and decreases in alcohol and tobacco use that contribute to the long-term physical and mental health benefits.

A 2012 review in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings (MCP) reports that physically active people live longer, have less chronic disease (such as coronary heart disease, hypertension, heart failure, and diabetes), and runners have a 19 percent lower risk of all-cause mortality. In 2014 a multi-university study with more than 55,000 adult subjects published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC), found an even greater, 30 to 40 percent, lower risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality for runners. Research published in the American Journal of Epidemiology on longevity in joggers vs non-joggers, with over 17,000 participants from the consummate study of heart health, The Copenhagen City Heart Study, found that male joggers live 6.2 years and females live 5.6 years longer than their non-jogging counterparts.

The Bad News

With all these positives, what excuse do you have not to lace up your Nikes and head out on the road (besides work, napping, or Game of Thrones)? Despite all the benefits, evidence of dangerous running-related side effects is accumulating. In the 1970s, Tim Noakes was the first to publish on the realities of running, which he mentions in his enlightening TEDxCapeTown talk. By 2012, the MCP review includes studies finding that “chronic intense and sustained exercise” can lead to patchy myocardial fibrosis, coronary artery calcification, diastolic dysfunction, and artery stiffening, with marathoners showing a 5-fold increase in artrial fibrillation and increased biomarkers of myocardial injury. However, the review concedes that these findings lack rigorous scientific support. Much of the reviewed data are from rat studies and most of the detrimental outcomes are reversible over time.

Mayo Clinic Proceedings article shows increased coronary plaque in male marathoners.

An intriguing finding published in 2014, shows that male marathoners actually have more coronary plaque than non-runners and it is unclear if this persists after the cessation of training. In summary, Dr. O’Keefe, et al., posit, “Accumulating information suggests that some of the remodeling that occurs in endurance athletes may not be entirely benign,” and it can take several years for elite athletes’ cardiac measurements to return to normal.

There are also supported differences in negative health outcomes between men and women. In a 2014 Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases (PCD) review, authors O’Keefe, Lavie, and Guazzi report currently unpublished findings that these plaques are not seen in women marathoners. Furthermore, the incidence of race death in marathoners is 5-fold higher for men than women. These differences may be attributed to better pacing by woman then men (Kim, J.H., et al., The New England Journal of Medicine, 2012)

This difference in pacing appears to be how we can keep endurance running healthy. And here comes the Catch 22: tell a marathoner to push himself farther, faster, and longer; but don’t go too far or too fast for too long and see how that works out.

The Diagnosis

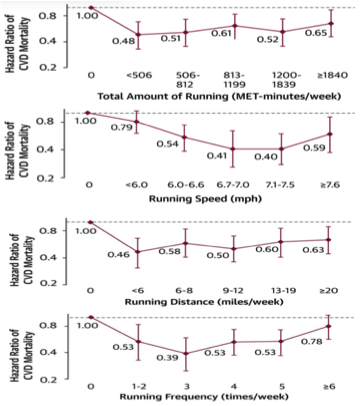

A February 2015 paper based on The Copenhagen City Heart Study in JACC and the 2014 PCD review, describe the U-curve of running. Based on this U-curve, the sweet spot to maximize health benefits is: 6-12 miles/week, 6-7 mile/hour pace (8.5-10 minute/mile), and 3 times/week for a total of 50-120 minutes/week. In addition, 30 minute runs are optimal while 60 minute sessions generate increased oxidant stress and vascular stiffness. However, the error bars are substantial enough in the PCD review to question the significance. Plus, if the data are largely self-report and gathered using different methods (Garmin watch vs Fitbit vs back calculated), there may be inaccuracy, especially over the small scales of time and pace.

There is a U-shaped trend but the error is large and data may be self-reported (O’Keefe, J.H., ProgCD, 2014).

If runners know they should observe some limits to maximize health, are they likely to follow these guidelines? In a 2014 study in the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy (JOSPT), Bruno Saragiotto finds that runners self-report difficulty limiting their training even though they believe it to be one of the two biggest contributors to injury (the other is stretching, which numerous studies have shown to have no impact on injuries). The belief in overtraining is true, excessive running can damage body structures and result in overuse injuries (Hreljac, A., 2005), but as Subject 49 in the JOSPT paper says, “…Running excites me when I start to run, when you are running you don’t want to stop, your body wants more, so you end up overloading your body and get injured… .” Well said, Subject 49. Running can be addictive and it usually takes more than the warning of negative outcomes to sway an addict.

The Prognosis

Running is a great way to stay fit mentally and physically and, no, running a marathon or two does not condemn you to an early grave. There are potential negative cardiovascular impacts of excessive running, but these require more rigorous and long-term research to verify. For now, if you stick to the sweet-spot of the running U-curve you will be running happily and healthily for years to come.